NEWS & PRESS RELEASES

| TITLE: The Linnaeus Apostles - Global Science & Adventure. The very first volume straight from the printers at a ceremony at the Drottningholm Palace, Sweden. DATE: 29th May 2007 ARTICLE CONTENT: In the company of the Speaker of the Swedish Parliament, Mr Per Westerberg and the Minister for Overseas Development at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Mrs Gunilla Carlsson and about 130 guests from many parts of the world, including the palace permanent tenants Carl Gustaf and Silvia Bernadotte, the very first volume of the monumental work The Linnaeus Apostles - Global Science & Adventure was launched. The presentation took place at Drottningholm Palace, Sweden's first World Heritage Site, because it was in the natural history and curio cabinets at Drottningholm Palace that several of the Linnaeus Apostles' collections were kept during the 18th century.

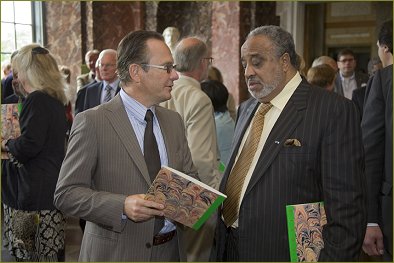

The highlight was the IK Foundation & Company's presentation of the first volume to the Swedish people through their official representatives the Speaker of the Swedish Parliament, Mr Per Westerberg, the Minister for Overseas Development at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Mrs Gunilla Carlsson and the head of state Carl Gustaf Bernadotte.

The programme with speeches and lectures is presented in its entirety below.

PROGRAMME (Presenter: Per Sörbom, The IK Foundation & Company) Your Majesties, Mr. Speaker, Mrs Minister, Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen, Dear Friends. Most heartily welcome to this little ceremony celebrating a major publishing venture that has been almost a decade in the making.

Being a historian of science and ideas I am naturally tempted to give you a two-hour lecture on the Linnaeus Apostles. But I will spare you that and instead introduce today's first speaker, who has played a key role in this project: OPENING ADDRESS (Opening address by Mr Ingvar Carlsson, former Prime Minister and Ambassador for the IK Foundation & Company and this project). THE LINNAEUS APOSTLES - HEROIC TRAVELLERS Your Majesties, Mr Per Westerberg Speaker of the Swedish Parliament, Mrs Gunilla Carlsson Minister of Overseas development, Ambassadors, Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen. It is an honour and a pleasure for me to welcome you all to this celebration today when we are able to present the first volumes of the great book project about the Linnaeus apostles. We are particularly grateful to his Majesty the King and her Majesty the Queen that we are able to have this presentation at Drottningholm. Carl Linnaeus inspired in the 18th century 17 of his students to travel through large parts of the then known world in order to document the local flora, fauna and culture. The 17 students covered all the continents and came to be known as the Linnaeus Apostles. This year we will be able to present to the world eight volumes, eleven books, totalling approximately 5.000 pages - indeed an extensive material - about the Linnaeus apostles. The work behind the publication is more than impressive - it is a major achievement. The project has been finished after nearly eight years of international cooperation. Manuscripts and forgotten letters to and from Linnaeus' 17 apostles have been collected and translated into English for the first time.

In 1742 as professor at Uppsala University, Linnaeus began to lecture on botany, natural history, dietetics, diagnostics and medicine. The young professor consciously broke with the medieval scholasticism and moved the lectures out of doors. His expositions were stirring and engaging. They were delivered with an ardent thirst for knowledge which attracted an increasing audience. From the group of approximately 400 listeners, an inner circle of students were gradually formed. They became devoted to the extend that, regardless of location, privation and hardship, they were prepared to collect plants and minerals and other information for their master. The Apostles had different positions. They were teachers, ship's physicians, clergymen, but they were all inspired by Linnaeus' forceful personality and his message of the new systematic biology. They were young - most of them between 25 and 35. During a quarter of a century - 1745 -1799 - the 17 Apostles travelled all over the world. The Swedish East India Company gave free passage to the Apostles while others sailed with Dutch, Danish and English merchant ships. Some of them paid for it with their lives. Others fulfilled their task collecting plants to verify a new revolutionary method within systematic botany - Linnaeus`sexual system which maintained that a natural order existed for the plants of the world. Besides, the Apostles brought back to Sweden and Uppsala samples of previously unknown minerals. The finds became important jigsaw pieces in the wide gathering of knowledge which then was to generate financial rewards and became an early basis for what might be called "the imperialism of knowledge". The Apostles' findings altered our understanding of the botanical world. They acknowledged the validity of a method which had been developed by one single person at a university which was not very well known at the time. Through his Apostles' material, Linnaeus was able to demonstrate that the sexual system could be applied the world over. Systematic botany provided all the plants with a natural order. Three of us here today are called "Project Ambassadors" and we have taken part in the birth of this unique sequence of books: Lars Gårdö representing industry, Olof G Tandberg sciences and myself the general public. However, the fact that we can now avail ourselves of the world of the apostles, is ultimately due to the IK Foundation & Company's director and editor-in-chief Lars Hansen. His capacity, energy and optimism is completely in line with Carl Linnaeus and proves that "the Spirit of Man" lives in our time. Warm thanks also go to Director Per Wahlström, to members of the editorial board who have tried to bring order into the 5.000 pages, to co-authors who have thrown light on the world of the 18th century and the traces it left and to all translators who have fought their way through difficult texts in various languages. Last but not least I thank all the financiers who have realised the significance of curiosity and knowledge that recognise no boundaries.

With these words I once again welcome you to this ceremony at Drottningholm honouring these young and heroic travellers. (Presenter: Per Sörbom, The IK Foundation & Company) Eivor Cormack one of our translators, much involved in the Sparrman volume, will now say a few words. (Mrs Eivor Cormack, translator of Anders Sparrman's Journal) SPARRMAN - MY MÉNAGE À TROIS Your Majesties, Your Excellencies, Ladies and Gentlemen. Anders Sparrman moved in with us a while ago now and soon became a constant but stimulating presence. Sparrman was an independent spirit, but what else to expect from someone who travelled to China on an East Indiaman, as surgeon, at the age of 17! At 23 he sailed for the Cape, "the land of Hottentots and Caffres", as he put it. His journals from that time, and the time he spent there after his voyage with Captain Cook, were published in the late 1700s, also in English translation, and they now appear again in this volume. My spell with Sparrman is confined to the 28 months he spent on Captain Cook's ship Resolution. He was on three voyages into the Antarctic and, in between, visited New Zealand, Tahiti, and many other Pacific islands. Sparrman multi-tasked - he was primarily a physician, but also botanist of course, zoologist, anthropologist and a humanitarian. His animal drawings are outstanding in their detail, and so are his written descriptions, whether of the various artefact's he collected or the facial features, hairdos, costumes and customs of the peoples he came across, even the way they amused themselves.

His medical know-how is evident in his discussions on scurvy, the scourge of sailors at that time, and expressed views on many other ailments. It also helped him restore Captain Cook's equilibrium after particularly arduous manoeuvrings when the ship had run aground - he did that with a typically Swedish remedy, en rejäl sup! He had an ear for music and language too and it is interesting how he compares the languages spoken on different islands, and how some islanders understood each other while others did not. He has drawn up lists of Tahitian and Celtic words that show similarities, and he quotes experts on Celtic and Sanskrit. Sparrman was driven by his mission to observe, collect and note everything, but sometimes his enthusiasm ran away with him and he did not manage to look after and properly record everything. He admits this, but comforts himself with the words "that happens more or less to every travelling Botanicus". Another time his conscience pricks him after a goose shoot on Christmas Eve, when he spent a whole day without "advancing botany", but justifies this because he was after all under the Captain's command, and the Christmas table had been much enhanced by the geese. He was intrepid and fearless. Once attacked by two ruffians on the island of Huaheine, he was robbed of his sword and stripped nearly naked, but fought back and got away, alive. The voyages to the Antarctic involved long spells in among the icebergs, often in thick fog or howling gales, with icicles festooning the rigging, snow filling the sails so they had to go about to shake it off to avoid capsizing - all on a frugal diet of salt meat and, towards the end, mouldy ship's biscuits full of weevils. He was a true Swede in his attitude to the way people treated each other - he argued for peaceful negotiation instead of confrontation and seemed scrupulously fair. He strongly opposed slavery and even testified against the slave trade in the House of Lords. He abhorred cannibalism which he witnessed with his own eyes but pointed out that it had happened elsewhere, too, and cited examples, including from the Old Testament. In the New Zealanders' warlike tendencies he thought he could see something of his own Viking ancestors. Nor did he lack an eye for the absurd. About rubbing noses in greeting he writes ".that my nose had been so very close to cannibals' teeth and that I had, nonetheless, been brought back home to Sweden safe and sound is still both an amusing and comforting subject for my thoughts." He recalls that on one occasion the ship's artist wanted to make a drawing of a local girl. Payment having been arranged, she came down to the cabin but took some persuading - in sign language - that all she was required to do was to sit for the artist! On board the Resolution there was not much time for entertainment. But on Christmas Day on the first voyage to the Antarctic, when they were surrounded by icebergs, some twice as tall as the ship's mast, the Captain's generosity had warmed the officers' cabin ".with punch, claret, Cape and other wines. so that all of us regarded the ice and hazards. with a more philosophical composure than usual". Then he goes on to describe how the sailors celebrated in their "bacchanalian mist" by indulging in the curious pastime, the noble art of self-defence, as practised by the English, namely boxing. So, although at times exasperated by his lengthy sentences, I did find him fun to live with. Thank you. (Presenter: Per Sörbom, The IK Foundation & Company) Mrs Kajsa Båth, daughter of Mr Per Wahlström, one of the directors and the Director of IK Foundation & Company, the indefatigable Editor in Chief, Lars Hansen, will now present the first volume of "The Linnaeus Apostles - Global Science & Adventure" to the Speaker of the Swedish Parliament, Mr. Per Westerberg, to the Minister for Overseas Development at the Ministry for Foreign Affairs, Mrs. Gunilla Carlsson and to Head of state Carl Gustaf Bernadotte (Mrs Kajsa Båth and Mr Lars Hansen, The IK Foundation & Company) PRESENTATION of the very first volumes - straight from the printers - of the international series of publications "THE LINNAEUS APOSTLES - GLOBAL SCIENCE & ADVENTURE" by the Director and Editor in Chief, Lars Hansen, on behalf of the IK Foundation & Company to

Please help us to pass on knowledge of lost landscapes and cultures by spreading the word as widely as possible about this magnum opus, "The Linnaeus Apostles - Global Science & Adventure". This the first volume of a total of eight, divided into eleven books under the title "THE LINNAEUS APOSTLES - GLOBAL SCIENCE & ADVENTURE". Volume five - SOUTHERN AFRICA, OCEANIA, ANTARCTICA & SOUTH AMERICA - publishes ANDERS SPARRMAN's journeys and meticulous descriptions from his various visits around the southern hemisphere, brilliant and interdisciplinary observations of great cultural and natural history value. The volume is beautifully illustrated with plates and contains two maps and two Tapa cloth samples from Tonga. (Presenter: Per Sörbom, The IK Foundation & Company) It's a great pleasure now to introduce an old friend, the translator Tom Geddes. For many years Tom has introduced Swedish literature to the English-speaking world. One of several reasons for inviting him is to underline how important the work of the translators has been for the success of this project. GUEST SPEAKER (Mr Tom Geddes, translator of Johan Peter Falck's Journal) A RELUCTANT ADVENTURER ON THE FRONTIERS OF RUSSIA: JOHAN PETER FALCK Your Majesties, Your Excellencies, Ladies & Gentlemen. It is appropriate that we are all speaking in English today since we are celebrating the publication in this world language of the many volumes of travels of the men who have come to be known as the Linnaeus Apostles. Eivor Cormack has talked of one of them, Sparrman; I am going to speak about just one other, but I hope we will give you some idea of the hardships and achievements of these scientists in pursuit of knowledge. Johan Peter Falck's journey was only by land - no dangerous sea voyage into the unknown. Yet Russia too was unknown in many respects, and certainly dangerous in the eastern border areas where Falck largely concentrated his efforts. I have entitled this introduction "A reluctant adventurer on the frontiers of Russia". The keywords are reluctant and frontiers. But first of all we must ask why Falck's book was originally published in German. All the apostles except two gave their accounts in Swedish. Daniel Rolander's expedition to Surinam was written in Latin and not published at all until now for the first time in English; Falck's German publication has been not only a linguistic limitation but also one of accessibility, given the relative rarity of the volumes in just a few national and university libraries. So all the Apostles have been rather inaccessible until this present publishing programme of their works translated into the lingua franca of English.

In the 18th century, of course, German and French were much more linguæ francæ, and this applied particularly to Russia. Falck's work, now translated into English as Essays on the Topography of the Russian Empire and due from the printers in the next few weeks, was originally published in German in St Petersburg by the Russian Academy of Sciences in 1785-6. There were particular reasons for this, but it was also quite normal for Russian academic and scientific publishing to be in German. Two of Falck's fellow explorers in Russia, who were themselves German, Gmelin and Pallas, had their various expeditions published in Russia in their own language. This was all in the reign of Catherine the Great, herself German, who continued the work of Peter the Great in introducing foreign influences, especially French and German, through the translation of books and the import of foreign expertise, while at the same time developing a sense of Russian nationalism in her people, and increasing their education and knowledge, not least of their own country. It is in this context that we must see Falck. Falck was a student of Linnaeus who had studied medicine in Uppsala and later became tutor to Linnaeus' son. He had already attempted an exploration of the Swedish island of Gotland, funded by Linnaeus, but failed because of the poor health that was to be a feature of his life. When Linnaeus was asked to recommend a curator for a natural history collection in St Petersburg, he thought of his now mature student Falck, who accepted the position and was soon promoted to professor of botany and director of the Botanic Garden of the Imperial College of Medicine. Falck's notes of his expedition were actually edited after his death by Johann Gottlieb Georgi, a German student who had accompanied him on the expedition and had become his most trusted assistant (and who, by the way, went on to write his own works on Russia, including a book on St Petersburg which clearly shows the influence of his mentor Falck). Georgi writes of Falck: Under Professor Falck's direction the [Botanical] Garden became rich in rare, particularly Russian, plants; his lectures on botany and materia medica received great approbation... He was invited by the Imperial Academy of Sciences to undertake a natural-history expedition through the Russian Empire... The expedition, from which he had high hopes for the recovery of his health, did not agree with him from the outset... He wrote in March 1769 ...'Gout, headaches and hypochondria have ravaged my body and agitated and depressed my spirit. While engaged on my work I can be seized by cramps to the point of fainting. Sleep eludes me. I feel like the living dead, and am additionally tormented by the thought that despite all the good will I can muster, I will be able to fulfil my obligations only unsatisfactorily, to the detriment of the Academy and to my own enduring shame.' Georgi regarded Falck as a "diligent, meticulous and expert observer", if a little chaotic, not least due to illness. But how did Falck regard himself? His account is prefaced by some poignant self-recognition: Aware of my modest capabilities, oppressed by illness..., content with my quiet and unstressful position as Director of the Botanical Garden in St Petersburg ... and subject to a pathological indecisiveness, I made it difficult for my friends to persuade me to undertake this important expedition. But my objections were mitigated by the thought that the change such salubrious regions would provide might well lead to the recovery of my health, by the prospect of indulging in my favourite pursuits on the journey and by the generous assurance of the College of Medicine that I would find my position ... open to me on my return, whenever that might be. Falck, of course, never did return. I will tell you now that he committed suicide, arguably from a sense of failure as much as because of ill-health. He was the only one of the Apostles to meet his end in this way, although several of them died on their expeditions, from disease or from capture and imprisonment. It is his suicide that was one of the main reasons for publication in German. Georgi had the formidable task of editing Falck's obviously unfinished and disorganised notes, and it must have been far easier for him to write them up in German, his native language, as well as fitting the Russian Academy's publishing programme and the country's increasingly international outlook. The expedition took place from 1768 to 1774. Falck was only 33 when appointed professor and director, 36 when he started out on his Russian travels and 42 when he died. But his magnum opus (I venture to call it that) is far more than the account of a natural-history expedition: it is a wide-ranging socio-economic geography. From St Petersburg he followed well-travelled routes to Moscow and beyond, soon venturing into lesser known regions, providing interesting observations on geology, agriculture and the urban economies and recent developments wherever he went. His journey took him across to the Volga, down to Astrakhan and the Caspian Sea as far south as present-day Azerbaijan, across the steppes and semi-deserts of what is now western Kazakhstan and up to the Urals, and as far east as the Chinese border. Travelling here was both difficult and dangerous. Not only physically, in having to wait for "winter roads", or travelling by boat down river instead of by land, but also in terms of safety, joining camel caravans to find the way, or with military escorts as protection against the eastern Hordes, who were still robbing or kidnapping travellers or making incursions into the expanding Russian territory which was protected by the so-called Lines. These were a series of forts and embankments designed to keep out the peoples Russia was gradually trying to incorporate or administer. Many of the forts had already become redundant, as the border moved, and others were expanding into the towns and cities they later became. Falck gives us a glimpse at a particular point in history into the process of civilisation and cultivation of landscapes previously occupied only by nomadic tribes. Georgi organised Falck's account into a region-by-region description, hydrology, mineralogy, flora, fauna and indigenous peoples, all prefaced by a chronological summary of the expedition. Most of the book can be read as a discursive account of travels and human geography. It is much more than a naturalist's handbook; and even the lists of flora and fauna contain background notes on their environment. In this English edition, the sections comprising only descriptive lists of flora and fauna have been left transcribed in their original German. The regional sections usually start with a description of the landscape, including geology, climate, river systems, their fish and navigational potential, habitation patterns and the people and their occupations, including statistical data gleaned from the various chancelleries. Falck surveys artisans and merchants in the towns, crops and the size of harvests, the prices of products, mining methods and various manufacturing processes. His remarks on mining in the Urals, its current state, previous failures and scope for development, are particularly significant for the history of Russia's mineral wealth, which was a prime factor in its economic and cultural expansion at the time. And even more fascinating are the areas beyond Russia's shifting frontiers in the steppe land which was gradually being taken over from the Mongol Hordes. His third volume includes some of the most intriguing material on the little known peoples of the eastern reaches of the empire: the Chuvash, Mordvins, Voguls, Basurmans, Ostyaks, Buryats, Kalmyks and many more. He gives detailed descriptions of their social customs: feasts, ordinary meals (not so ordinary to him), their marriage arrangements, religious beliefs, shamanism, their houses, tents, clothes, weapons, their animals and medical practices, including some bizarre cures for anthrax in both animals and humans. Falck was also a keen linguist, or comparative philologist. He interpolates words in local languages for produce and objects, and he collected further systematic samples of various languages which he tabulates for ease of comparison. For the lesser known languages, Votyak, Cheremiss and the like, he simply transcribed what he thought he heard, and finding an English equivalent orthography was just one of the many difficulties of translating Falck's wide-ranging interests. In fact, the major difficulty throughout this book was spelling. Usually it is style and idiom, and indeed these posed their own special problems, since I wanted to avoid archaisms while also avoiding modern anachronisms. The book was printed in a Gothic font, the printer had made some errors, and some letters are not easily inter-distinguishable because the printer had used a mix of different fonts. German words were easily recognisable: the problem was the presence of Russian words and proper names throughout the text. I had to check every single name, whether personal or place-name, to determine an English spelling. And there were hundreds of them! A further problem of place-names was that many appeared in an inflected form of the name qualifying a generic feature, such as a fortress or a factory (interesting in itself, because in Falck's time this was what many places still were, before they developed into towns), and Falck's and Georgi's knowledge of Russian was obviously too rudimentary for them to get the agreement right between adjectival name and the feature it qualified. Another aspect of place-names is that they can change fundamentally, especially in Russia. I had to identify every place on maps not only to establish its spelling, but whether it still existed or whether it had changed. I have retained the names as they were in Falck's time, but have appended a list of more than 80 names that changed in the course of Russia's history. To follow Falck's journey now on detailed maps is an interesting exercise in historical geography. The other main difficulties arose from the specialised vocabulary of the manifold fields that interested Falck. Translation difficulties often exemplify the unique qualities of a text, and they certainly exemplify the breadth of Falck's range. From obscure minerals and geological formations such as coralline rivers, to foundries, leather tanning, silkworm breeding, the fermented mare's milk and millet beer of nomadic tribes, ways of catching different kinds of sturgeon, and even a fish for which I found no translation (muxun, which still appears on English-language Moscow restaurant menus untranslated). Falck displays both a sense of humour and critical acumen. His recommendations for improvements include new agricultural methods, different crops or reorganising settlements. He clearly had a sense of the ridiculous, as when he describes his own efforts at riding a camel or a Meshcheryak carter being entrusted with a sick horse to cure, but slaughtering and eating his patient. Had he lived to see publication, I suspect he would have included even more such instances to enliven his account. Falck spent five and a half years on this expedition. It would have been gruelling for anyone in good health, but he had many bouts of illness, including a winter in Moscow and a long period in Kazan at the end. His penultimate trip was to the spas of the River Terek in present Azerbaijan, partly in an attempt to improve his health, but always continuing his economic analysis, and foreseeing there the possibilities of what we would now call tourist development (a man ahead of his time!). He himself, as well as Georgi, referred to his hypochondria, in the eighteenth-century sense of "melancholia", but his physical symptoms were obviously debilitating, and his mental state must often have verged on depression. Despite all this, he has given us not only descriptive lists of flora and fauna but a unique and comprehensive insight in the true Linnaean tradition into the social and economic conditions of the furthest regions of the expanding Russian Empire, so little known even in Moscow and St Petersburg, let alone outside Russia, at the time. Georgi provides a graphic picture of Falck's suicide - a knife to the throat followed by a bullet to the head. I think Falck's motivation was a mixture of chronic illness and a double sense of failure: he knew he had not achieved as much as he wanted, and to cap it all, he had been recalled to St Petersburg and instructed to end his expedition and release some of his students (even Georgi) to fellow-explorer Peter Pallas. We must never forget the difficulties and hardships these "Linnaean apostles" endured, nor the great sadness Linnaeus himself must have felt as he learned of the deaths of some of his best and favourite pupils, his "apostles", who died if not exactly for him, then in the cause of science and learning. (Presenter: Per Sörbom, The IK Foundation & Company) Carl Linnaeus did not travel extensively when he reached a mature age. Instead he chose to send his pupils, apostles, as he liked to call them, out into the world. His letters tell of his impatient waiting for parcels and reports from the disciples dispersed all over the world. Mr Håkan Wahlquist, Curator of the Museum of Ethnography in Stockholm, has agree to tell us something about these collections. EXHIBITION (Mr Håkan Wahlquist, curator, Museum of Ethnography, Stockholm) LINNAEAN CURIOSITIES Your Majesties, Excellencies, Distinguished Guests. The Apostles that Carl von Linnaeus was instrumental in sending to various corners of the world were a part of his impressive project to describe how the natural world was all a part of God's grand design for the universe we inhabit. Linnaeus needed to prove that what he claimed to be his discovery of what this design actually looks like would in fact hold true for the whole world, a world that during his lifetime quickly became much bigger, through voyages of discovery, and infinitely much richer and more surprising in natural variation. His apostles were expected to bring home to him, for his scrutiny and classification, as rich examples as possible of the world that nature, and then ultimately God had fashioned.

But as we know the Linnaean project did not stop at that. His work was also meant to serve useful purposes. He was interested in "economy", in how people made use of the natural resources God had presented them with, and even though his pupils surely, to the best of their ability, concentrated on collecting and documenting the flora, fauna, geology etc. of the areas they were decided for, many of them were also keen observers of the peoples they met, and some of them in turn brought back with them objects that were fashioned not by nature but by human hands. These were called "artificial ones" or more commonly "curiosities." In many cases these objects of curiosity were as astonishing to the spectator as were ever the dried plants or the prepared animals brought home. They were objects of a kind that in many cases had never been seen before in the west and surely not in this country. But mostly these artificial objects were incidental to the natural ones, which the demanding benefactor of the apostles, back in Uppsala, mostly craved. And most of the apostles returned without any, if they returned at all. We should remember the extreme difficulties under which most of them travelled; the dearth of funding and surely transport capacity they had to cope with. Thus, only a handful of the pupils Linnaeus dispatched managed to return with ethnographic objects, not surprisingly the ones that could enjoy the best transport facilities. Accordingly objects from these journeys are rare and treasured objects in those museums and collections that can pride themselves of possessing such "curiosities". The Ethnographic Museum in Stockholm is one of them. These objects often open up windows to the past, to transactions with peoples sometimes encountered for the very first time.

These collections of ours originate from four different travellers, which all belong to the latter part of the Linnaean project, which continued also after the Linneaus' death in 1778. One can easily claim that it was the most successful phase, not the least because all those who left then returned alive from their journeys. The ethnographic collections they yielded have reached us on three different occasions, on three different routes. The Ethnographic Museum finds its origins in the collections that the Academy of Sciences started to build, upon its foundation in 1739, also a brainchild of Carl von Linnaeus. Over the years ethnographic objects occasionally found their ways to the Academy archives, but there was no real program to create or encourage such collections. Not until Anders Sparrman (1748-1820) in 1779 became curator of the Academy collections, did they acquire some kind of prominence, because then his collections consisting of some 50 ethnographic objects were entered into the Academy cabinets. Formally the objects were accessed only in 1799. Unfortunately, history tells us, as it turned out Sparrman was neither a particularly talented nor interested curator. Sparrman had been on three long journeys. In his youth in 1865 he had travelled all the way to China, but this was before he had met Linnaeus and been converted to his cause, Thus, no objects returned from that journey. His next journey, however, resulted in more tangible collections. Sparrman travelled with James Cook on his second journey (1772-1775), which not only brought him closer to Antarctic than anyone had been before him but also to warmer areas in the South Pacific, where he could complement his botanical and other acquisitions with strange, beautifully shaped and ornamented objects from the Maori on New Zeeland, as well as from the inhabitants on such island archipelagos as the Marquesas Islands, Tonga, Tahiti, and New Caledonia. Before and after his journey with James Cook he spent long periods in South Africa which also resulted in ethnographic collections. Very likely the total collections from this period of his life could have been more substantial had he not lost a big box with objects from Tahiti, that he actually suspected Cook of having divested him of. At the same time exotic objects could very well have been meant for the market. The apostles were poor, short of funds and always in need of subsidiary incomes, and objects of the kind brought from the islands of the South Sea were much in demand. At the same time there was less pressure to collect them for scientific purposes. The Linnaean system was never meant for their classification, and they could never be used for proving it.

The third journey made by Sparrman took place in 1787 and brought him to the coast of Senegal in West Africa. It was a journey with a complicated background which strangely enough tried to combine the establishment of a Swedish colony there to take part in the slave trade, with ideas to establish a utopian society in the interior of Africa built on Emanuel Swedenborg's ideas. Sparrman and his companions were actually all staunchly against the slave system, a position Sparrman had taken already during his time in South Africa. In a way they were thus most unlikely Swedish colonists, and those countries already on the colonial map of West Africa, had anyway no inclination to allow additional players onto the scene. No colony was thus established, and for that matter neither any utopian God's Republic. Slavery was eventually forbidden and abolished. The Swedes furthered this issue somewhat in giving evidence to the House of Lords in London about the atrocities they had witnessed during their journey. Sparrman returns to Sweden after only three months in Africa, with 25 curiosities in his luggage, objects most likely acquired during a week-long journey inlands from their camp at the French slave trading depot at the island Gorée, not far from today's Dakar. Sparrman was not the first of the Linnaean apostles to travel with Cook, however. Daniel Solander (1733-1782), Piteå's most celebrated son, had been recruited to participate already in his first journey (1768-1771). Solander had then teamed up with Joseph Banks, a Briton who used his wealth to further research into the natural sciences, something that progressed via observations, taking notes, depicting and collecting. Solander had already before the journey made London and the intellectual circles there his home, rather than Uppsala and Linneaus. And so it would continue also afterwards. His collections, including his ethnographic ones, remained in London, and were in many ways inseparable from those of Banks. The "Solander collection" that the Ethnographic Museum possesses, was accordingly called the "Banks collection" when it was accessed in 1848. And there is a third even older name for it: the "Alströmer collection". Johan Alströmer (1742-1786), son of Jonas Alströmer (1685-1761), both early industrialists and interested patrons of science, knew Solander well from Uppsala. During a stay in London 1777 he was presented an ethnographic collection by Banks, originating from the South Sea. It was brought to the museum (and library) that his father had created in Alingsås. Banks donated big collections of natural objects to this institution, as well. In 1779 a fire devastates the museum but the ethnographic objects survived and were kept within the family until they were handed over to the Royal Academy. In turn they was passed on to the Museum of Natural History that had been formed out of the Academy collections, in which the embryo for an independent Museum of Ethnography could be found.

This particular collection contains almost 70 objects. It is more or less hopeless to find out which objects were acquired by Banks and Solander respectively in the field. A separation may even be pointless since they worked so closely together. The collection actually also contains objects that could not have been acquired by any one of them in the field. They must have been brought to London by the second Cook expedition, only then to be acquired by Banks. A third celebrated pupil, who left ethnographic collections behind, was Carl Peter Thunberg (1743-1828). He was away on his journey for longer than any of the other ones (1770-1779), staying for a year in Japan, for even longer periods in South Africa, making enough long halts at both Java and Ceylon to produce local floras. The ethnographic collections come from Japan (some 100 items) and South Africa (a slightly smaller number). The lack of precision in the numbers given by me is related to the fact that the original documents are far from clear as to "who brought what from which place", and in some cases the collection of one and the same traveller might be spread out through a much bigger collection. The so called "Uppsala collection", which the museum received in 1874, illustrates this, even though Thunberg's Japanese objects are neatly ordered in the beginning of it. Taken together these objects well illustrate Thunberg's confined and controlled life while in Japan, where Westerners, i.e. Dutch, were not normally allowed to stray outside the little artificial island in the Nagasaki harbour, Deshima, where they were allowed to go ashore. Many of the objects are not only small, to be sneaked away, but appear to be such that Thunberg could well have been allowed to acquire for his own personal use. Some of them he did use himself. Thunberg's objects had, thus, originally been given to Uppsala University. The same thing had happened to the items brought to Sweden by the last disciple we will have reason to mention here; Adam Afzelius (1750-1837). A pupil of Linnaeus, and thus trained in botany, he was docent in Eastern languages. Tired of intrigues in Uppsala he had moved to London in 1789, where Banks still exerted great influence. In 1792 he was hired by the Sierra Leone Company and sent to Sierra Leone on a typical Linnaean enterprise; a combination of collecting specimens, sent to Banks in London and Thunberg in Stockholm, and finding out what the colony might produce and provide; basic science and utility combined. Bad health forced him to return to London after only a year, but in early 1794 his is back in Freetown, this time to stay for two years. War between England and France is raging and French ships attack Freetown. The town is gutted; Afzelius work is laid in ruins, his collections and diaries are lost. During the last year he starts anew, a frustrated work that we can follow in his surviving diary. But luckily to us he manages to acquire a unique ethnographic collection of some 50 objects. In 1799 he donates all of it to Uppsala University and subsequently it forms a part of the transfer that the University in 1874 makes of all its exotic objects. The transfer is made to the Museum of Natural History, to the ethnographic collections there, which in just a few decades will form the material basis for a national ethnographic museum. When you have a look at the small selection of objects we have brought here today, you will find that in outward beauty they range from skilfully carved and decorated objects to a plain bow, without string together with four arrows, without any decorations at all. Objects, like these ones on display, are often just for the eye, but they can also be objects for the mind if you just give them a chance and listen to the stories they harbour. Thus, behold the bow and arrows, the most inconspicuous objects displayed to today and listen to what they can tell us: They originate from Cook's first journey. The ship with Cook, Banks, Solander and all the other ones onboard has crossed the Atlantic and left Brazil, behind. They are about to brave one of the most dreaded parts of the journey, rounding Cape Horn, the southernmost tip of South America. In April 1520 Magellan had been the first European to reach these areas and to see the open fires ashore, around which the inhabitants huddled, accordingly naming the area Terra del Fuego. The relationship between the crews passing its straits and fjords, rounding its southernmost tip, had since then turned violent. When Cook came there a new era of scientific explorations had replaced a period of attempts at colonisation, but more was to come. On the 15th of January 1769 Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander are brought ashore. The Endeavour has anchored outside the south eastern tip of Terra del Fuego. They quickly meet two Indians, most likely belonging to a group called Haush. The two men lay down the spears they carry, a gesture of good will it is assumed, or submission we can guess. Anyway, the meeting turns out well, not the least because the two Europeans have brought brightly coloured glass beads and ribbons with them, which they distribute. More Haush men, women and children turn up. Three men are brought on board and offered brandy, which they prove unable to drink. At least these Haush have probably not been in any contact until now with the world that soon will disrupt and destroy their societies. During the coming century in the North West the Kawéskar will suffer from punitive expeditions sent against them from passing ships, new settlers and seasonal hunters. North of them, towards Patagonia, the Selknam will be evicted from their open grassy landscape by sheep farmers who actually hunt them like animals, a fate that will wipe out the Haush as well. And in the South the Yamana will be subjected to disastrous missionary activities disrupting the very foundation of their society, moving them to congested settlements where deceases, until then unknown to them, can do their work. The following day Solander and Banks together with a few men leave for a botanical excursion. The hills in the west attract them. They will soon experience the violent changes that the weather can undergo in this area, and they are almost trapped. The journey is almost coming to an abrupt end for Solander, as it had done to so many of his predecessors. But they manage to struggle to a campsite and safety. Two servants of Banks, though, freeze to death when on an ill planned attempt to rescue some other crewmembers. On the 20th of January 1769 Solander and Banks again leave for a botanical excursion. They encounter some simple huts, which they study. From its inhabitants they acquire some objects before they return to the ship; a bow and for arrows. (Presenter: Per Sörbom, The IK Foundation & Company) When the time had come to present the first volume of The Linnaeus Apostles this magnificent building was the obvious place as a number of the objects sent home by the apostles came to be kept here, in the curio cabinet. So, on behalf of the IK Foundation & Company I have the honour to thank their Majesties for so graciously letting us use this beautiful location today. I would also like to thank The Bank of Sweden Tercentenary Foundation, the Royal Court and the Museum of Ethnography for their valuable support. You are now invited to have a look at our exhibits and taste the 18th century-style refreshments, described in more detail in the programme sheet. GUIDED TOURS In addition to the exhibitions at Rikssalen, IK's guests are invited to join guided tours of the Drottningholm natural history and curio cabinets. Numbers are limited. Tours begin at 12.30, 12.45, 13.00 and 13.15. REFRESHMENTS A buffet inspired by the 18th century voyages - taste the unique Sailors' fruit cake and mature cheese, part of the fare on Captain Cook's ship; fruit and berries to keep scurvy at bay; all washed down with lingon berry (cranberry) - flavoured water or South African wines from the vineyard of Constantia, the well-known and oldest vineyard in South Africa, founded in 1682 by Catharina Mechelse, who arrived at the Cape from Lübeck as a widow. Her second husband was eaten by a lion, her third murdered and her fourth trampled to death by an elephant! The wines served today are: Steenberg Merlot and Steenberg Sauvignon Blanc.

While enjoying this fare, spare a thought for Sparrman who on his travels visited the vineyard and was much revived by its wines - a highlight in his otherwise extremely frugal travel diet.

MUSICAL ENTERTAINMENT Eva Maria Hux (violoncell) plays 18th century music for solo cello by M Marais, J S Bach, C d'Hervelois, S Lanzetti, A Vivaldi, J B Loeillet, G B Sammartini, J L Duport, D Gabrielli, G B Pergolesi.

THE PRESENTATION The IK Foundation & Company in association with

CONTACT: For additional information about this article, please contact IK Photo: © IK Foundation & Company/T Sandin. SEE ALSO: The Return of the Linnaeus Apostles The Linnaeus Apostles - Global Science & Adventure

|

No comments:

Post a Comment